Fulbright Guiding Question and Reflection: History influences how we view ourselves and the present. Intimate cultural surroundings and artifacts are powerful reminders of the complexity, innovation, and humanity of our forebears. How do Peruvian students interact with museums to build a deep understanding of their connection to the past, and how does that connection foster national and cultural pride?

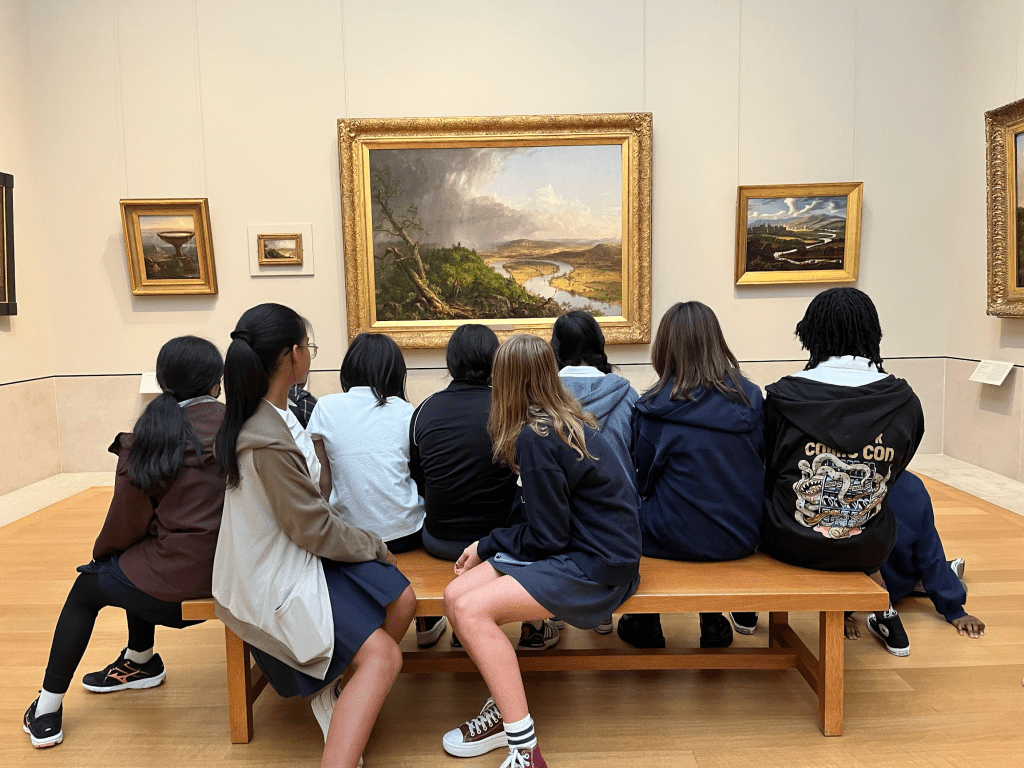

I went to Lima and Cusco with a curiosity about how a culture so rich in history connects to these through its museums. In New York City, where I teach, I hardly ever present a topic or encourage learning without integrating a museum into the process. As an interdisciplinary teacher, I like to draw on a huge variety of sources, and museums are places where experts reside. An educator, in my opinion, benefits from the modesty of recognizing the expertise of others. And of course students crave opportunities to study real things.

My real research began in Cusco though I do have some observations about the experience students in Lima have with museums: Mostly they do not go to them. Lima is a congested city and transportation through it comes with significant barriers to travel. Peru doesn’t have a national system of school transpiration, so teachers interested in field trips must arrange their own transport. While a 2022 study found that 23% of visitors to Peru’s Open Museums were students, the number of school field trips must be much lower, and this number probably refers to students going independently, of college and high school age.

This is an unexploited resource. Students growing up in Peru might delight in having a close connection with artifacts surrounding them. The national curriculum places significant emphasis on ancient Andean cultures, and integrates study of them into social studies across the grades. Lima is flush with museums and archeological sites, owing to the palimpsest of cultures which have built upon themselves over the millennia. Adult patrons with means can visit Pucllana, an ancient site of the Lima culture, while dining.

Cusco is a very different story. The city is smaller and the archeological sites, being international destinations for tourists, are well-developed and more accessible. Most of them have agreements with schools to provide free entry with the accompaniment of a teacher.

However, the interpretive signage was lacking, and when present it was not at all geared to children, even adolescents. Sacsayhuaman, a beautiful Inca citadel on the rim of the city, allowed our Cusqueno students free entry, but without a guide to provide explanation and relevance. The site itself had almost no signage, and an opportunity was missed to connect the students to their heritage. I remarked that the students all had phones with them and may have benefitted from a series of QR codes with explanations. Perhaps I or you should apply for a grant to build an explanatory website or pamphlet.

Nevertheless, despite the paucity of resources available at Sacsayhuaman, the students cared about it and fortunately I had read up on it in advance. They touched the massive stones and marveled at them. They contemplated how special the construction was, and how mysterious it is that the procedures for stone carving have been forgotten. They slid down inclined stone hills with glee.

But nothing was as impressive as their solemnity amidst the ancient grotto where they offered libations to the ancient Inca god Pachamama. Obviously their behavior indicated a profound relationship with the ancient world of which they see themselves part. I felt that if they knew more about the academic facts of the place, that that loving relationship would be even more satisfying. It reminds me of what Richard Feynman said in his essay, The Value of Science:

“Poets say science takes away from the beauty of the stars — mere globs of gas atoms. I too can see the stars on a desert night, and feel them. But do I see less or more? The vastness of the heavens stretches my imagination — stuck on this carousel my little eye can catch one-million-year-old light. A vast pattern — of which I am a part—perhaps my stuff was belched from some forgotten star, as one is belching there. Or see them with the greater eye of Palomar, rushing all apart from some common starting point when they were perhaps all together. What is the pattern, or the meaning, or the why? It does not do harm to the mystery to know a little about it. For far more marvelous is the truth than any artists of the past imagined it.”

How can we not feel obligated to teach children what we know? Are we to imagine only the aged and academic deserve knowledge of our shared history? Is it going to be a privilege for the elite to know about the very ruins that cram our city? Is it going to be for tourists and pilgrims and archeologists while the people drinking the tap water are shut out?

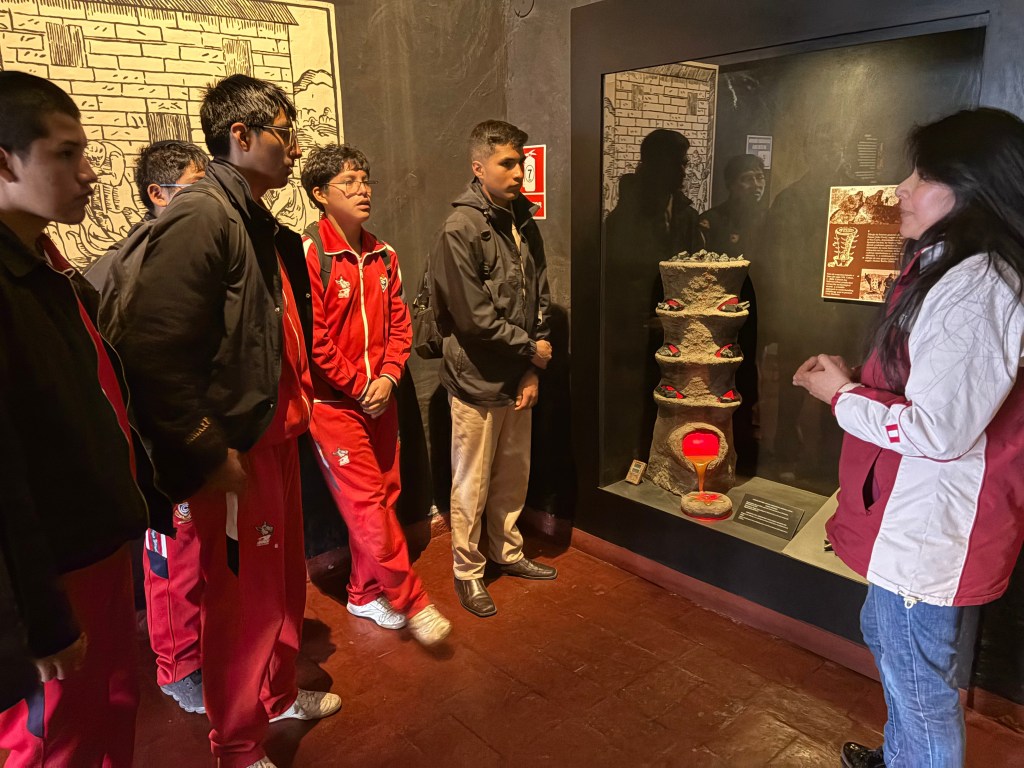

At the Inca Museum the feel was different. It was a testament to how such a field trip should be. A dedicated guide took our school form and had been awaiting us. She asked questions, she inspired inferences, she patiently and sometimes animatedly told stories of legends and truths. The kids were in rapt attention, curious, smiling, hushed. The power of the museum was evident in the triangle linking the students, the guide, and the artifacts.

I was impressed by the eagerness and the intentions but I felt we should be doing a better job letting our students intimately know our treasures. The pride was there, but it was inchoate, aspiring. I think placing a greater emphasis on the “glocal” cultural artifacts that are everywhere in Peru will foster a confidence and self-worth that seems at least one purpose of education. Imagine growing up in Rome and not knowing what the Coliseum was for.

Leave a comment