Before going, I soaked up some Peruvian art in New York City.

Day 0:

New York is a treasure chest of connections to the global community, past and present. The Metropolitan Museum of Art recently reopened its long-awaited Rockefeller Wing, exhibiting art works from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. Prior to going to Peru, I availed myself of the marvelous examples of Inca and pre-Inca Andean artifacts on display.

Wherever you are, there is almost always a museum for inspiration! Curated objects are not merely beautiful, but speak of the people who made them, their values, their techniques, their history and insights. I realize that as a New Yorker, I’m spoiled with some of the finest collections in the world, but you’d be surprised at how meaningful museum artifacts are everywhere. In each case they have been kept for their significance to professionals, and the stories they tell are deep ones.

People these days are concerned about how these items were acquired. I don’t have the scope here to weigh in on this important topic, except to say I admire the way that people all over the world can exchange meaningful, important objects in a cross-cultural, mutual appreciation. If I were required to see such objects only in Peru, or Egypt, or Japan, I would know less about those places, and be more isolated in the world.

Day 1:

Then it was off to the airport to meet my first colleague and embark on the intellectual, cultural, interpersonal journey of Fulbright TGC. I had spent the year learning about global education, building a community of American educators, and planning for my research in Peru.

The Fulbright Teachers for Global Classrooms program offers American teachers a critical opportunity to expand their practice by establishing a community of teachers across the US, providing an online platform and discussion groups for them to learn and practice global education. Then, teachers meet in DC for a symposium before becoming part of the cohort of one particular nation, whose educational systems, people, and culture the teachers will get to know.

Fulbright exchanges are intended to build productive, paradigm-shifting relationships between the artists, scholars, and teachers of the United States and counterparts in the rest of the world. It is a privilege to represent American techniques, ideologies, and attitudes in Peru and to develop professional relationships which can enrich the lives of both countries’ students.

I joined the Peru cohort when my original placement — in Morocco — was canceled due to a suspension of federal grants that was lifted but not in time for Morocco, and felt very lucky to be sent to such an amazing country, filled with history, community, and geographic splendor.

My wife was born in Peru, so I have some experience with the country already — for instance I have been to Machu Picchu three times! — but going in the capacity of a professional was new to me, and I am grateful to the American people and government for allowing me to have such a meaningful experience. I built lasting relationships with educators and students and look forward to meaningful collaborations with them to enrich the lives of people in both countries.

Days 2-3:

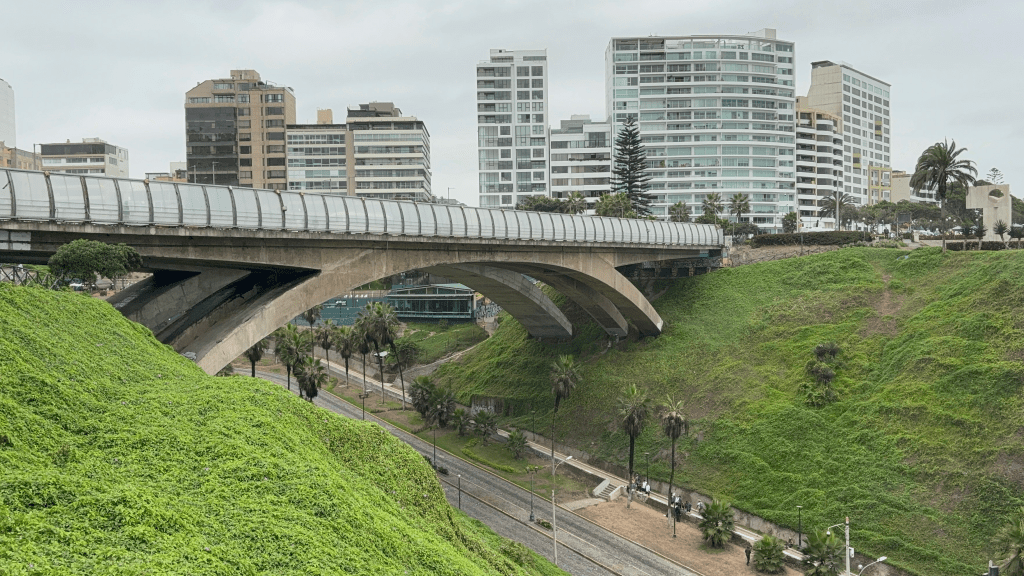

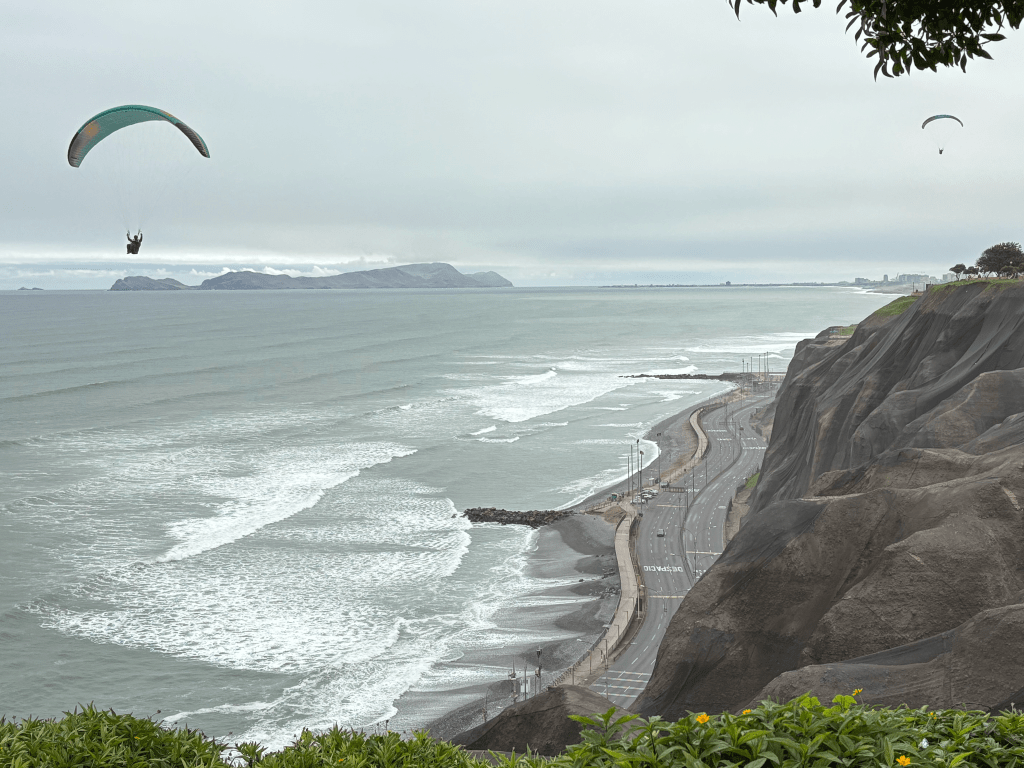

Lima is on the Pacific coast. The entire western coast of South America is a location of immense geological activity, as the Pacific plate is subducted underneath the continental plate, accounting for mountain-building, volcanic activity, and earthquakes. I experienced my first earthquake on the sixth floor of my Miraflores hotel – a 5.7 – and enjoyed the experience as an emblem of the powerful forces at work beneath the city.

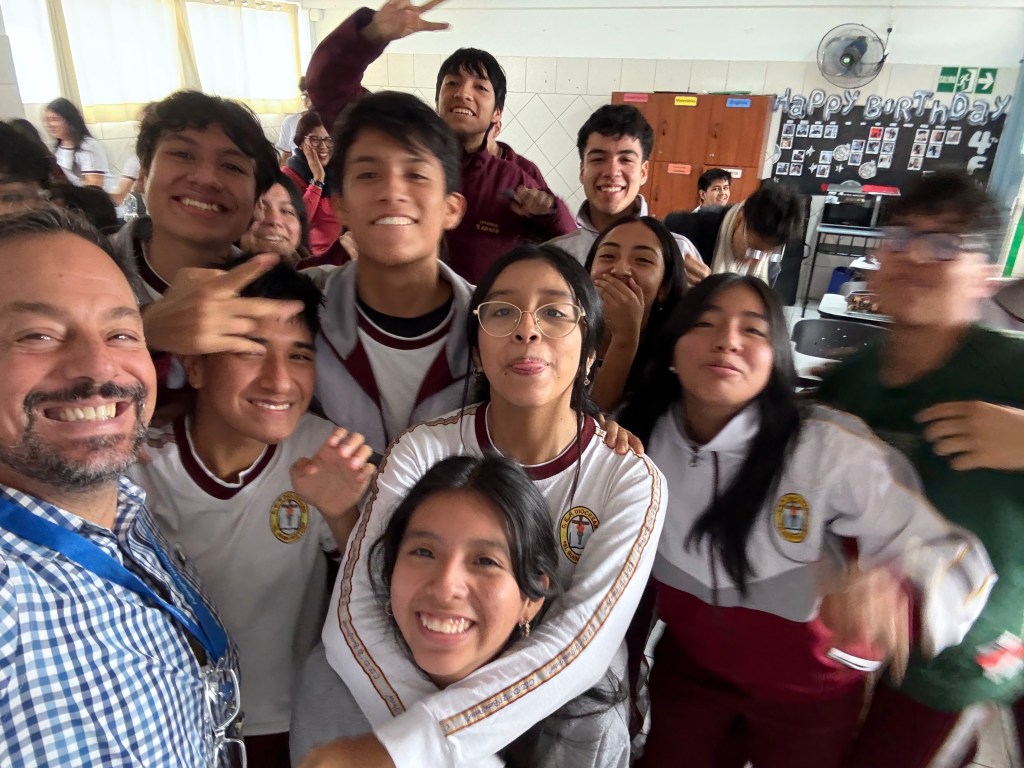

Visiting schools in Lima, our cohort of twenty US teachers could immediately sense the cultural hospitality of the nation. Schools awaited us with performances, sample lessons, and refreshments. Unanimously, we American teachers were struck by the positive relationships that students had with each other and with their teachers; their eagerness to participate in musical, dance, and hospitality functions; and their warmth. It was a powerful experience for us from a nation plagued by school shootings and intruder drills. It’s something Peru is doing extremely well.

This year Lima had four restaurants on The Fifty Best Restaurants in the World, owing to at least these two things: its incredible variety of agricultural and aquacultural products, and its phenomenal syncretism, a word for the mixing of cultures which characterizes Peru. When Pizarro brought the Spanish in the 16th century, they stayed. At times they played by the typical colonialist playbook, dismantling the Inca temples to construct cathedrals which still stand. But they also left art, and language, and a western constitutional structure. Not only this, but Peru welcomed significant numbers of Japanese and Chinese immigrants who influenced in particular the culinary reputation of Peru. Lomo Saltado is symbolic of this profound syncretism, made from the potatoes and tomatoes Andean people cultivated, the beef which the Spanish brought, and soy sauce from the Japanese. Depicted here are some dishes I enjoyed in Peru, and even some from Kjolle, which was ranked #7 this year. There is a panoply of diverse ingredients, preparation styles, and the unique genius of the establishment’s chefs.

Days 4-7

When people visit Peru they are understandably struck by the impressive stone work left behind by the Incas. Any ancient civilization, however, is standing on the shoulders of giants and the prowess of the well-known Inca has got to be understood as predicated by a dozen marvelous, innovative, long-lived, and well-studied cultures which left their marks all over the country and integrated their art, achievements, and technological wizardry into the continuous thread of Andean civilization we see today.

The Chavin, the Wari, the Mochica, the Chimu, and the Nazca people – to name just several – all created lasting physical and environmental artifacts, but also contributed to the agriculture, language, and social organization of the Central Andes.

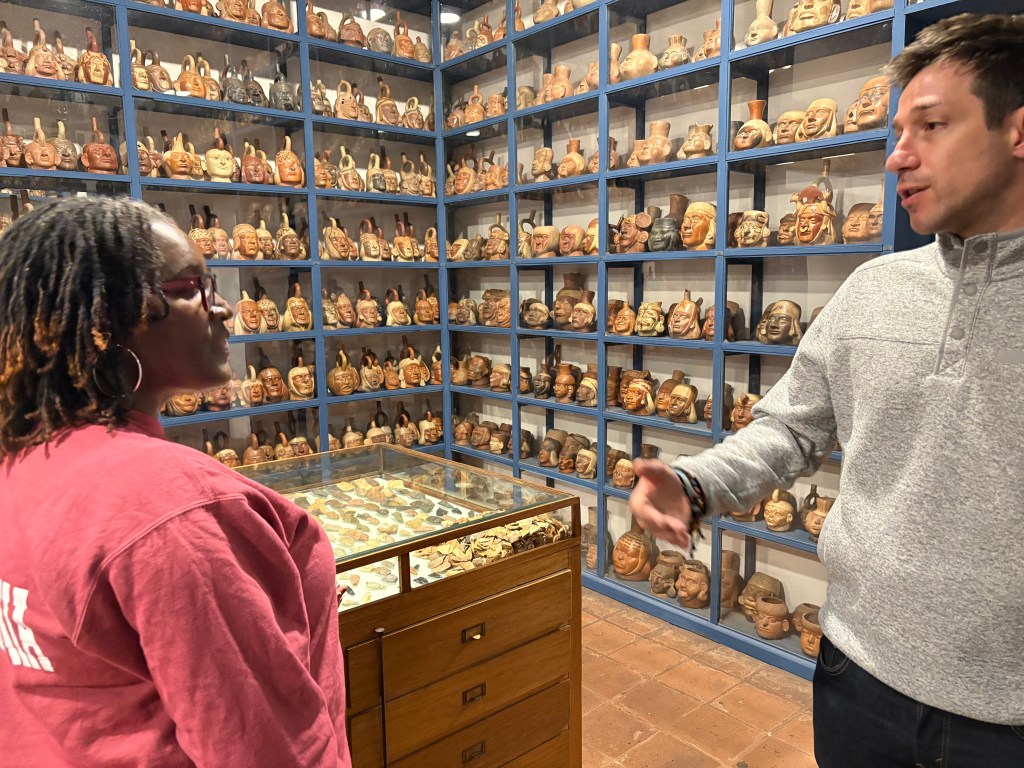

Visiting the Larco Museum of Lima, many of the physical artifacts can be appreciated. These Mochica stirrup bottles depict fishing, surgery, gathering honey, marital relations, and countless other scenes from ancient life compose a library of human knowledge.

Peru’s cultural history is an inheritance that its people and students can draw on for identity, pride, intellectual curiosity, and world heritage. But so can we. It doesn’t matter where you come from to appreciate human innovations and insights. UNESCO‘s world heritage program is a testament to how cultural contributions are important to all of us. The thought that these Moche ceramic heads are only relevant to people genetically descended from them denies our common humanity.

In fact, the scholarship surrounding the artifacts in the museum depends on experts from Peru and elsewhere in the world, each contributing academic expertise which illuminates the human, cultural inheritance which is otherwise obfuscated under the layers of the interposing centuries.

These boys are looking out into the future. As the world becomes more and more interconnected, their future matters to us as much as ours does to them. The face of the future is the face of the students in school all over the world.

In some ways American students have it easier than they do. In my school in Cusco some teachers charge money for worksheets. Our schools are comparatively well-funded.

But that doesn’t mean that everything we do is superior. While our material resources are more ample, there are aspects to the human resources in Peru that remind us how much work is left to be done in America in terms of community development.

I intend to further study the ways that other nations build community and mutual respect.

Like all major cities, Lima cannot be adequately explored in a lifetime, let alone the week I had there, but you can expect incredible museums, sights, activities, and more.

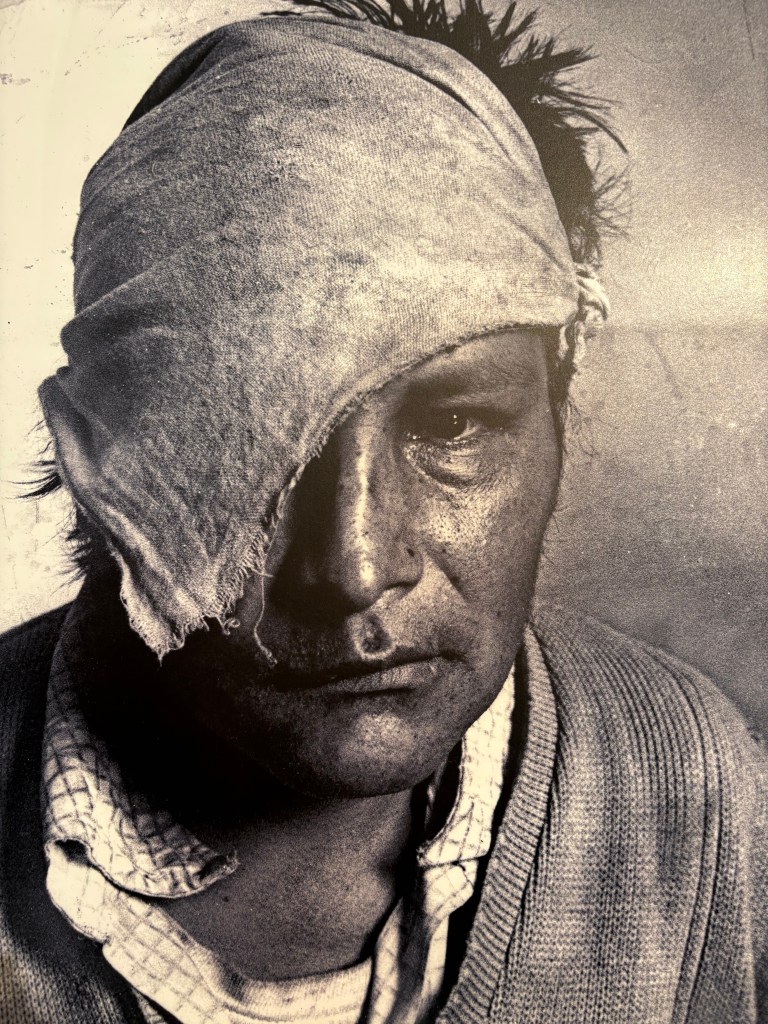

In addition to visiting many schools brimming with happy, earnest children, we explored other cultural sites in Lima, including the Museum of Memory, which tells, within its brutalist architecture firmly anchored into the Pacific cliffside, of the difficult times Peru endured during the 1980s and 1990’s when the country experienced a spate of violence and injustice.

Then It was goodbye to Lima.

Saying goodbye to the elementary school children to whom we taught Head Shoulders Knees and Toes was a powerful reminder of how most children want the same things.

Day8-9

In Lima we reveled in the culturally immersive experiences at schools, institutions, and even the US Embassy to brainstorm with top Peruvian educational officials.

After a week in Lima our cohort divided into mostly pairs for experiences in host schools throughout the country, with intentions to observe and teach classes, participate in professional development for teachers, and come to know more intimately the communities in which we were placed. Craig and I felt fortunate to be placed in Cusco, a beautiful town of ancient stone nestled at 11,500 in the Andes. Cusco was the capital of the Inca civilization and presents itself as such. Like Florence, Italy, it’s ringed by mountains and roofed with terra cotta tiles, narrow, boisterous streets, and tourists from all over the world.

We happened to be in Cusco for important, ancient celebrations related to the winter solstice, and the streets were peopled and vibrant with parades, dances, and music.

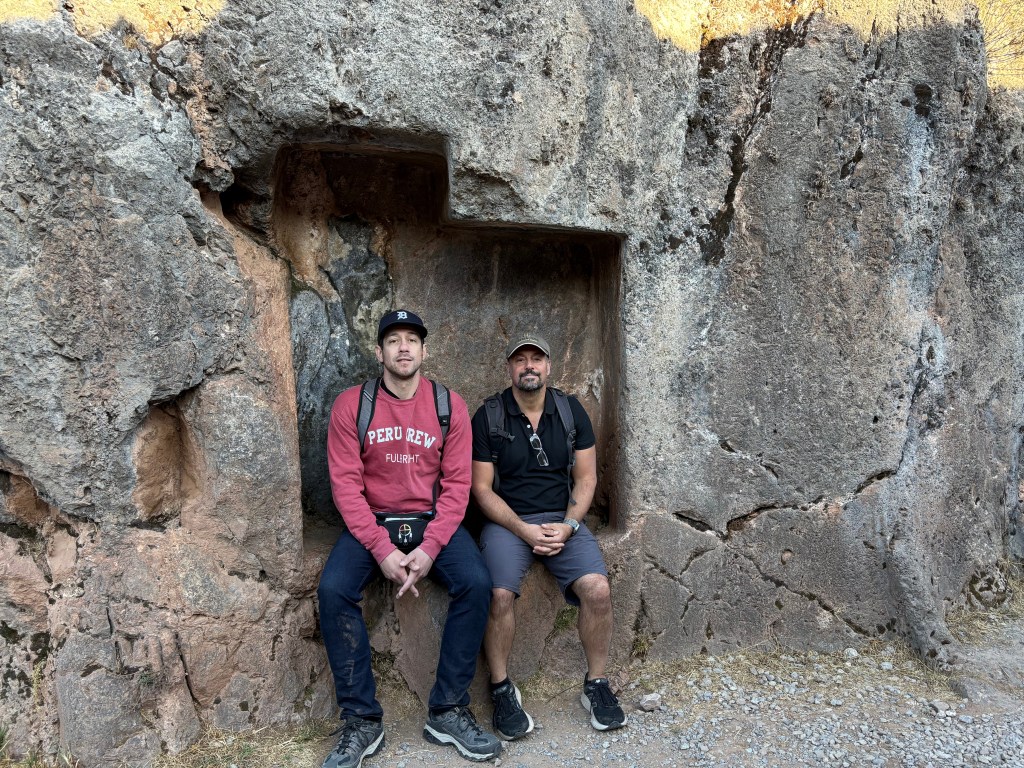

On our first day in Cusco, my colleague Craig Gallow and I took our new students on a field trip to Sacsayhuaman, an Inca citadel in the city. Our school placement was the oldest high school in Peru, the Colegio Nacional de Ciencias, founded by Simon Bolivar in 1825, an all-boys school with a reputation that precedes it everywhere.

For me, the most poignant, outstanding moment from this Sunday field trip was the opportunity to watch as twenty teenage boys all participated in an extemporaneous ritual to pour libations at the archeological site. Each boy took the bottle of wine and solemnly paid tribute to the loving earth mother, Pachamama. Most of the them are Catholic. This was also a part of them, the willingness to be grateful, to be a community, to do something sacred in a sacred place. I was very moved.

Paying tribute to Pachamama

We were thrilled to take the students to Sacsayhuaman, but felt that the site was inadequately interpreted for visitors. Outside of a simple pamphlet and very rare and occasional signage, if you hadn’t read in advance about the citadel you wouldn’t learn very much about it besides its impressive physicality. I would like to return and spearhead an online repository of information visitors can access remotely with QR codes, as is done in museums all over the world.

On the same weekend we also went to Machu Picchu. It can be done in a single day, albeit with a traveling intensity that most people would not embrace. We were awoken at 4 AM to take a bus to Ollantaytambo, several hours away, to take a train for a few more hours to the town of Aguas Calientes. From there we took a bus to the archeological site and spent a good portion of the day exploring the parts of the ruins we had reserved.

We were lucky enough to be there on Peru’s winter solstice, June 21st, when an ancient ritual would take place. A priest would tie the sun, whose arc across the sky was getting shorter and shorter, to a stone hitching post, thus saving the people from darkness. You can still see the hitching post and also visit the notch in the mountains from which the early sun rays would hit it on the solstice, Inti Punku — the sun gate. Craig and I did walk there and enjoyed the exertion.

There is no denying the impressive landscape and architectural wonder of Machu Picchu, which was probably a summer estate of the Inca elite.

Days 10-12:

Part of the day Craig and I taught lessons to high school boys, led professional development, and observed Peruvian educators, but we would not escape the hospitality of including us in the school’s parade presence. With costumes and dance steps and wigs and masks, we did as the Romans did and immersed ourselves in the delight of celebration.

Because Peru is in the southern hemisphere — though mostly equatorial — its solstices are opposite ours, and the winter solstice, which fell this year on June 21st, was especially crucial for the Inca.

Watching these boys dressed for the parade in their personalized outfits, replete with stuffed animals and other indicators of their innocence and identity, felt paradoxical. They are teenage boys, 15 and 16. They own cell phones but didn’t take them out. They do what their elders request and participate in this parade, demonstrate this ancient game of whipping each other’s calves — and there were welts afterwards! For some reason I felt that this demonstration was emblematic of the positivity of Peru’s youth. There wasn’t the slightest speck of animosity. They engaged in this game as a reverence to their ancestors, as a display of their continuity with a civilization which still feels more or less alive, despite the Western impression that the Inca are no more. It was not as much a pantomime as enactment, a ritual, a visceral exploration of what it means to belong. It was beautiful.

What a once-in-a-lifetime experience to be part of the annual celebration of Inti Raimi, which corresponds to the winter solstice. Schools empty for each to be present in the numerous parades, dressing up, dancing, playing instruments. It is a profound experience to be participating in something that has such ancient roots and which has been interpreted so lovingly by a community which personalizes it in every way. It was incredible to see our students be leaders in their city.

Martha is a powerful educator, transcending how some Americans might conceive of the role as a teacher from simple classroom instructor to mentor, guru, and loving community member. She is adored by her students and is generous with her own time, taking them on excursions, leading them in performances, and offering counsel and love to them.

In the midst of all of this hullabaloo, we still had time to visit the central market of Cusco, which — as all markets — reveals how the locals live and eat and work. We were not there for souvenirs as much as for a better understanding of the day-to-day lives of the people whose children we were educating.

Cusco is a remarkable city and it is difficult to put into words or pictures what is so remarkable about it. The Inca called it the Navel of the Universe. It is full of such excellent stone work — the archeologist Hiram Bingham said of its stones that they were “fitted together as a glass stopper is fitted to a bottle.” But it is also a place that brings people together, bringing handicrafts and crops from distant communities, bringing tourists and academics, and bringing pilgrims. For such a small place, it seems like a crossroads, tucked in the Andes but traversed by Swedes, Japanese, Americans. Being a student in such a place has advantages and disadvantages; while in one sense you have access to people and ideas from everywhere, in another sense you come face to face with profound economic disparities, for while you probably have never even visited nearby Machu Picchu, the people around you are spending thousands and thousands of dollars to travel the world and do so. It is a reminder that you are materially poor. Many of the students at our school have parents who sell souvenirs on the street, earning just enough money to survive. One virtue of schooling is that it can be a catapult from one economic stratum into a higher one.

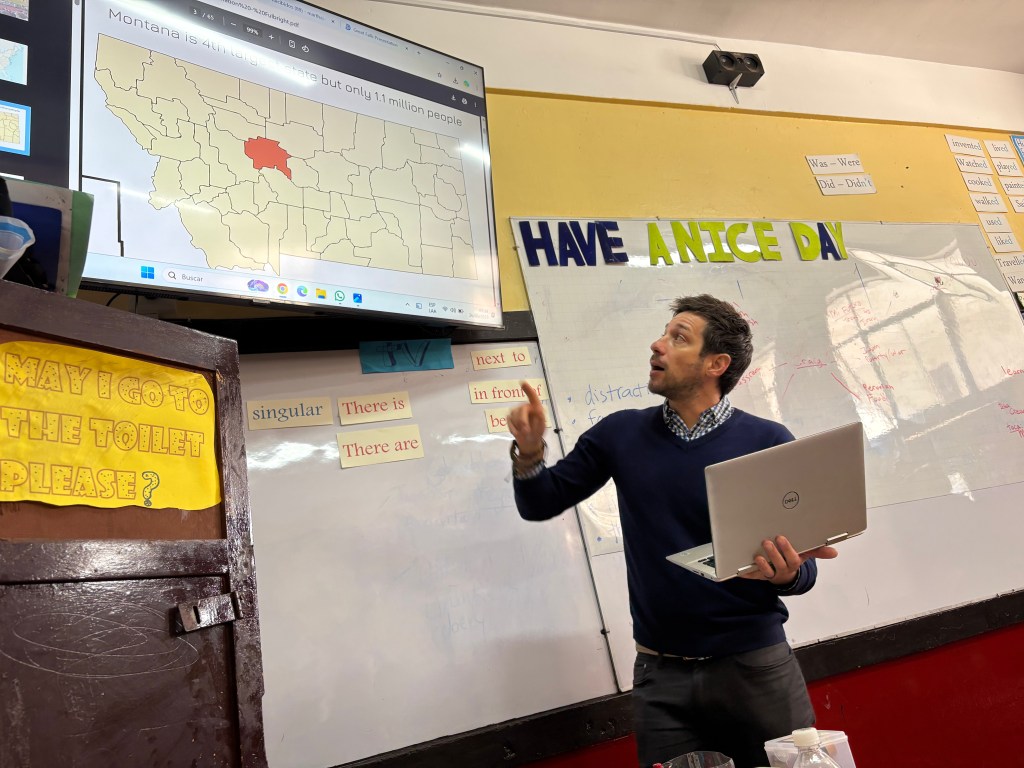

Craig and I taught and observed many lessons and also gave professional development on interdisciplinary education and using the See Think Wonder protocol. The school was welcoming and motivated. We got the feeling that American habits of professional development were comparatively robust and that teachers in Peru often lack access to opportunities to enhance their craft and explore new options to bring content and activities to students. On one day, our lesson was cut short because a ministerial representative was coming to view how tablets were being integrated into the classroom, although no formal training had been offered to support the technology. I’ve seen that kind of oversight in New York City too, but it seemed there was no protocol for charging or storing the devices and I imagined this due to a lack of support structure and training.

Day 14:

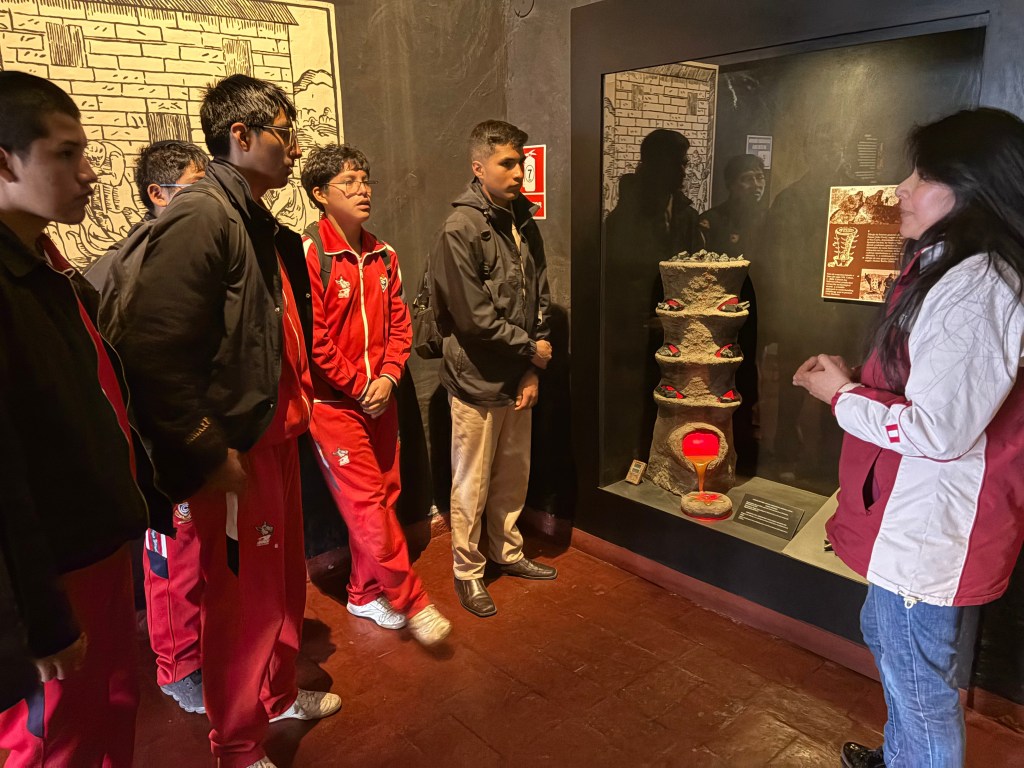

We took the students to the Garcilaso Museum. This was important and part of the answer to my research question: How do Cusqueno youth come to appreciate their immense cultural and historical heritage with the museums and monuments which surround their lives? The museums all give free guided tours to school groups if they are requested in advance. These students are getting a historical and archeological timeline from ancient geological history forward. Peru’s history is one of cultural changes, empire, colonialism, independence, and more.

Going to museums with young people is a highlight I frequently experience as an educator and this time in Peru was no different. It is often a surprise how little experience children have with museums, even though they reify and legitimize the abstract lessons they encounter in school. Frankly, schools should make a stronger effort to integrate museum visits and experts into their curricula. Our Colegio students were exceptional listeners and participated diplomatically and eagerly in discussions we had about history, colonialism, art, and technology. Not one of them was found in a corner on his phone or zoning out; nothing was wasted on these young men.

Day 15:

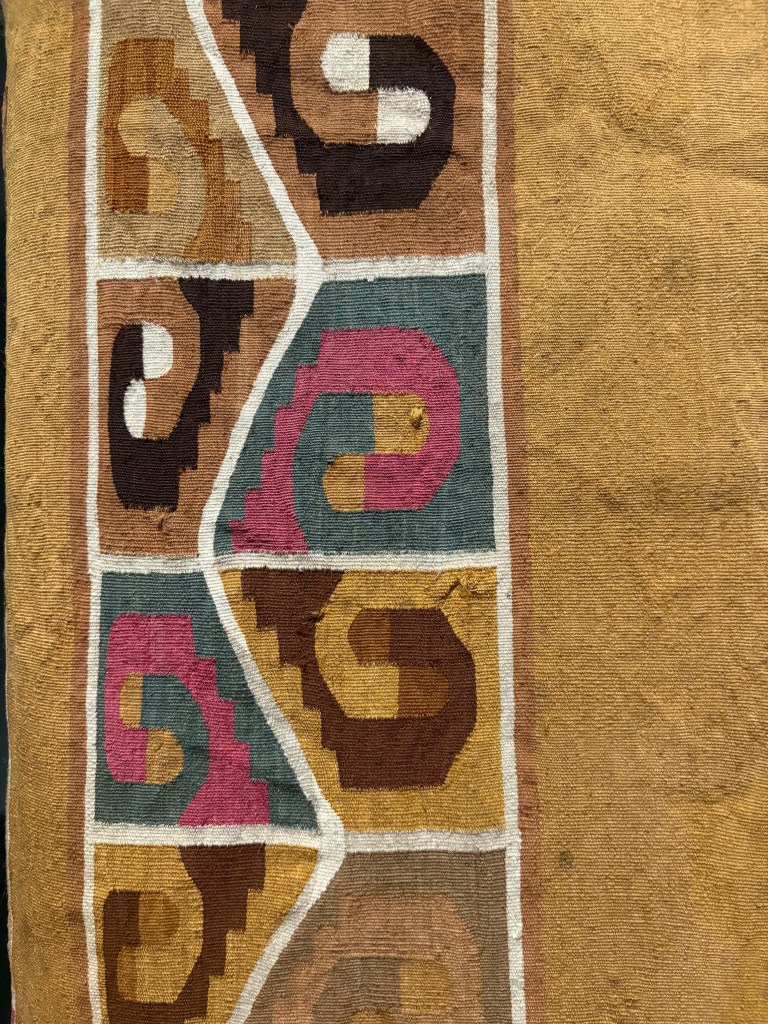

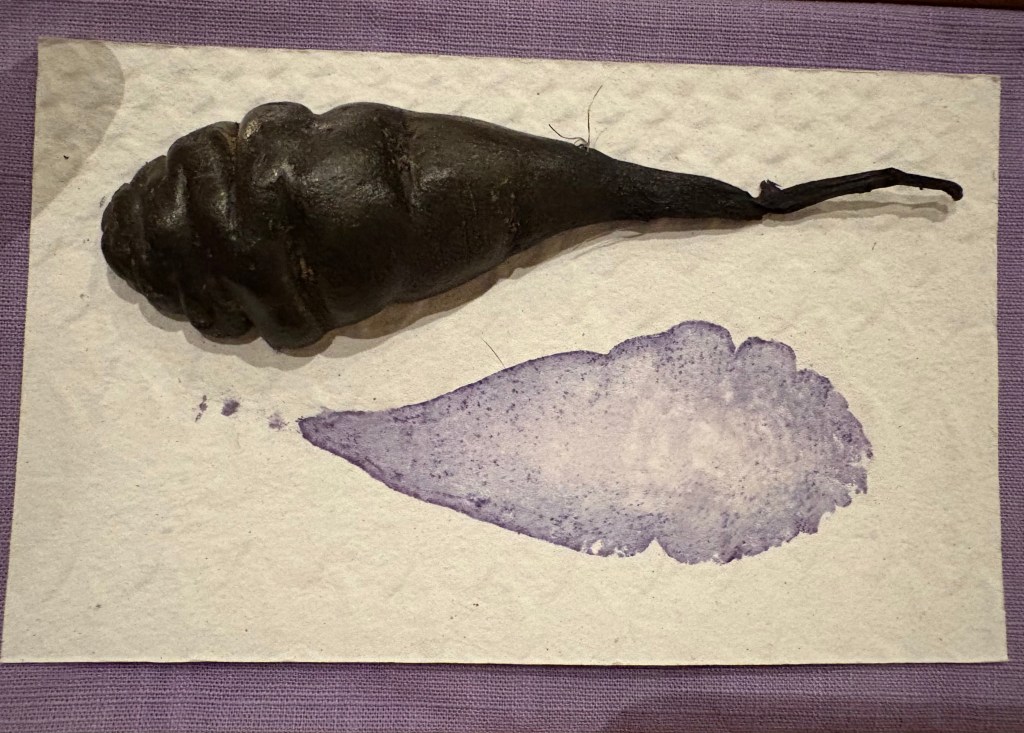

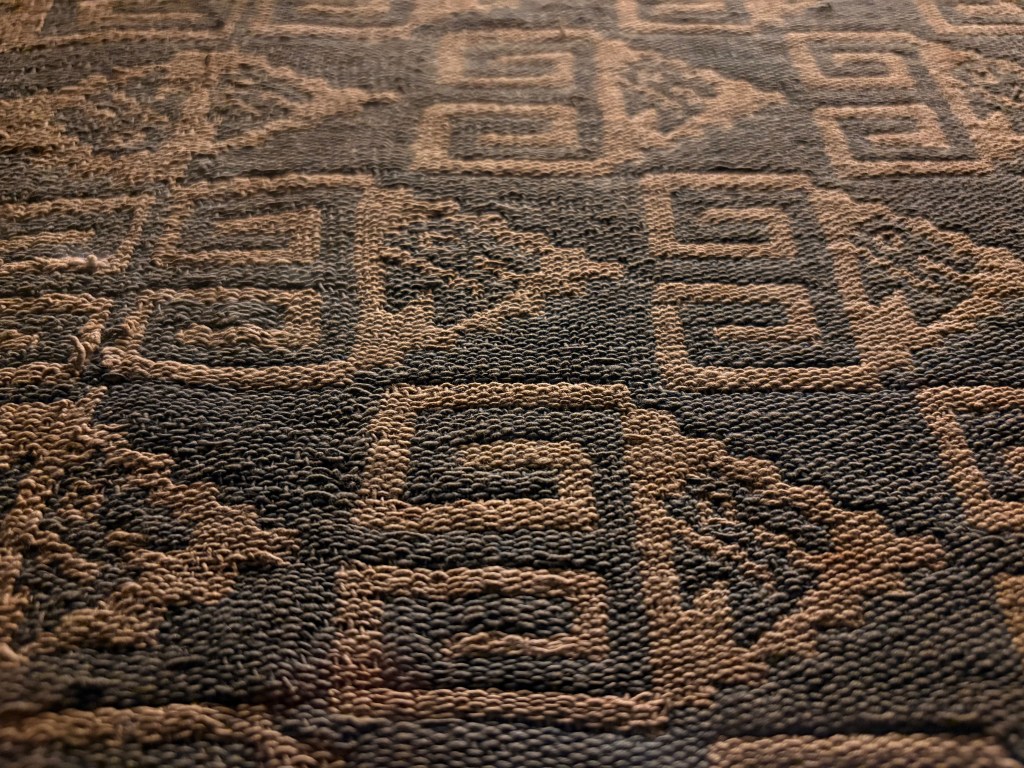

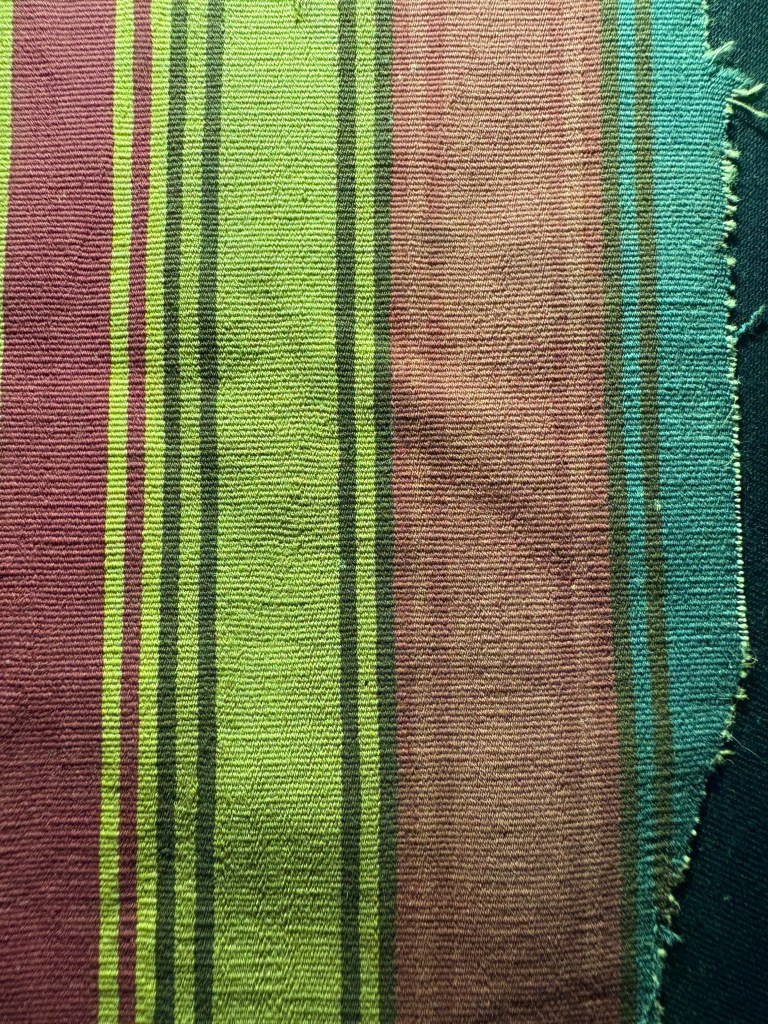

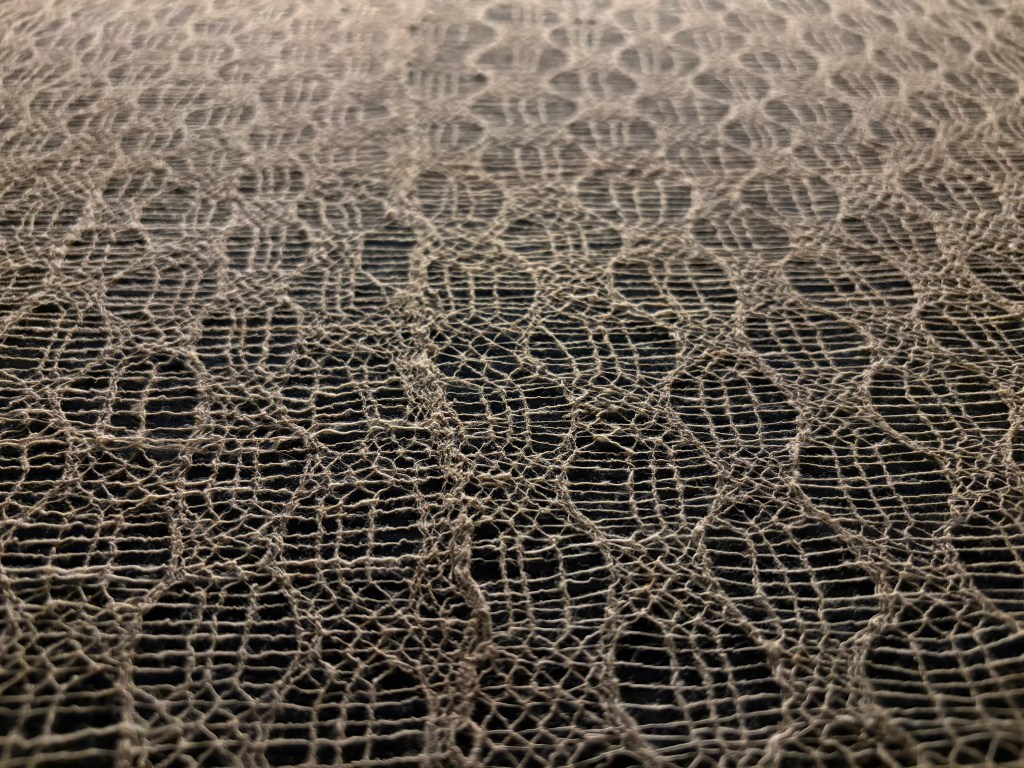

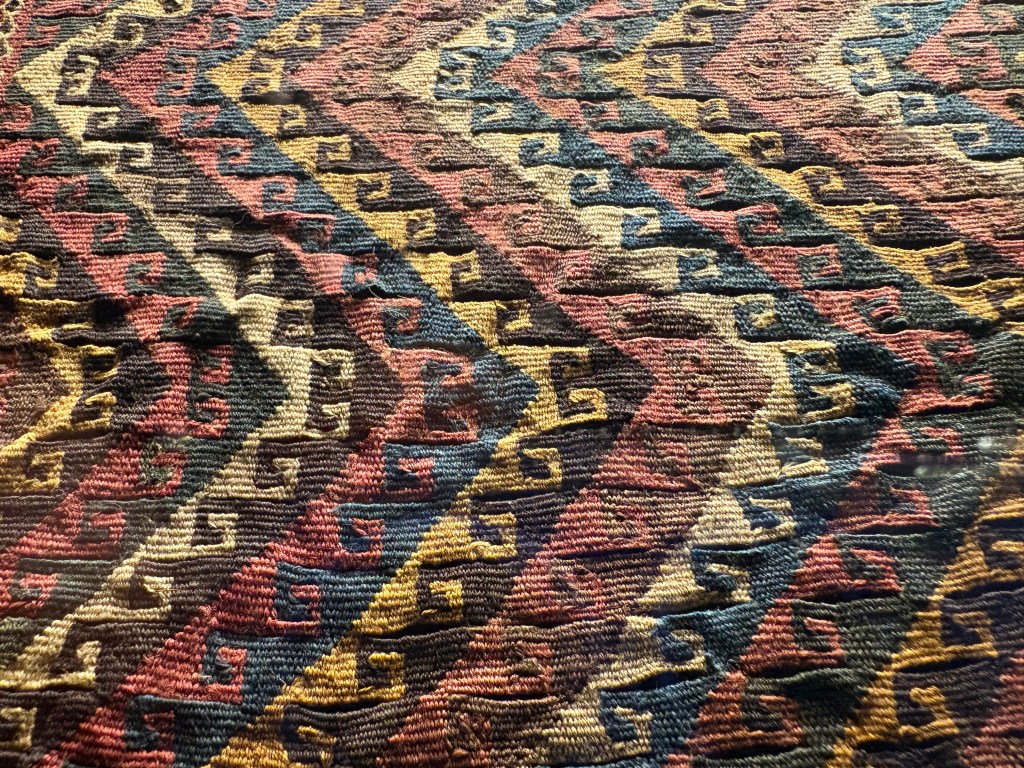

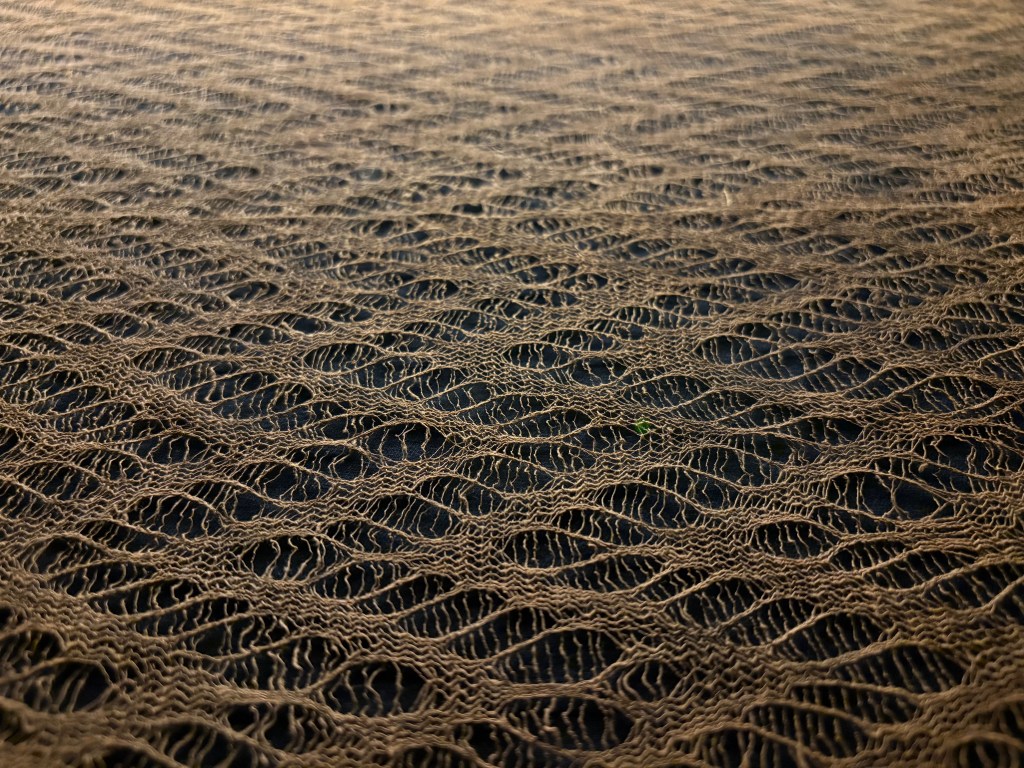

The textiles of the Andes were, according to the head of Harvard’s Peabody Museum, the most sophisticated in the world until the advent of computerized weaving. Given the large number of ancient world cultures, this is saying a lot. The tradition predominantly made use of camelid fibers. Alpacas, Guanacos, and Vicunas are relatives of the camels, which all originally evolved in North America. Their hair is suited to being twisted by hand into threads and woven into beautiful designs.

You can find museum examples of extraordinary Andean textiles both in Peru and in museums outside of it, many of them thousands of years old. They were often used to wrap the mummies of important people, to distinguish rulers and aristocrats, and just as blankets and clothing we can all appreciate personally. What is most intriguing is that the specialized skills of creating such peerless textiles are still very much alive in the Quechua communities surrounding Cusco. They’re expensive too. A handmade table-runner might cost $500, a poncho $1000. And that’s alpaca! Try to buy a coat in Vicuna — a fiber finer than cashmere that was exclusively worn by Inca nobility — and you might pay $40,000. The disparity between the budget of the rich and the budget of the majority of Peruvians is stark.

We met an American student who had studied for an entire semester and felt that she was only beginning to appreciate Cusco. I felt that way too. The sheer volume of celebrations taking place when we were there suggests that Cusco’s identity is as ceremonial as practical. Throughout the school year there are so many parades and other festive activities that weeks of educational time are dedicated to their preparation. It may seem counter-productive or illegitimate, but I think of it as an expose of world-class project-based learning. The students become ambassadors to the world of their culture and — even more important — connect themselves to history and community.

With so much nostalgia for the beauty and meaning of our experience with these precious students, we left Cusco to meet our colleagues in Lima once more before a return to the United States.

Days 16-17:

The International Research and Exchange Board (IREX) planned a complex and packed professional experience for us, and its members have my sincere gratitude. We braved the famously congested traffic of Lima in a bus to traverse the city and explore its riches. We spent half a day at Cesar Vallejo college of education to build relationships with practitioners and graduate students. This was valuable time, though much of it was absorbed in the pomp and circumstance of awards and presentations. Our time in the classrooms was the most interesting, and I tried to lend my thoughts to the young teachers about their power as teachers, that they were building minds in their elementary school classrooms and that the effort they put into lessons and the creativity they employed would leave their personal stamp on the growth of a whole society. They were so joyous I knew I could trust the future.

A final highlight before my departure was visiting the Amano Pre-Columbian Textile Museum.

It was founded by a Japanese businessman named Yoshitaro Amano who, after settling in Peru, dedicated himself to collecting and preserving pre-Columbian textiles from various ancient Peruvian cultures. The museum, which opened in 1964, is internationally renowned for its collection and for its role as a bridge for cooperation between Japanese and Peruvian researchers.

I highly recommend this and every other museum I was privileged to learn from. Teachers are artists whose art is about learning from the vast world and then figuring out how to make it meaningful to students. Fulbright provided opportunities for us to learn, and the many years of my teaching future will all be touched by this experience.

If you are curious about the exchange programs which Fulbright offers to teachers, scholars, and artists, please follow the link and leave your own stamp on what it means to represent America and enrich the world with sharing our insights and experiences in meaningful ways.

Leave a comment